A Delicate Balance Between Law and Compassion

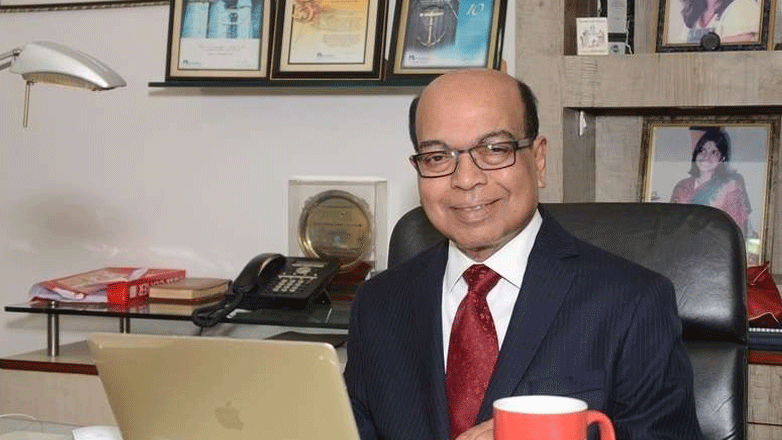

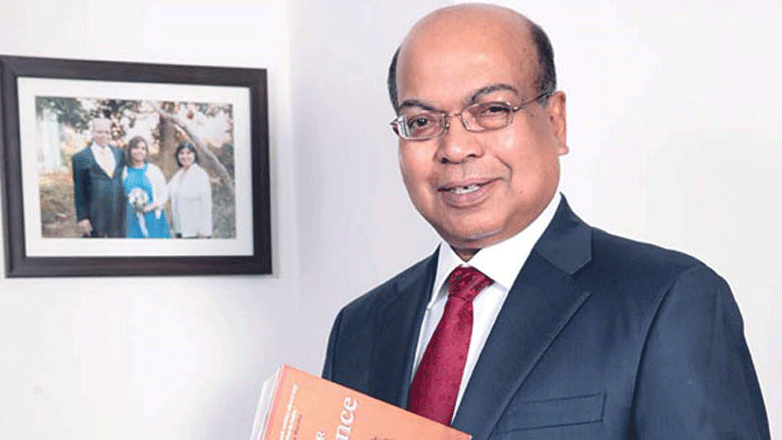

Seven months after retiring as the 50th Chief Justice of India, Justice D.Y. Chandrachud finds himself at the center of an unusual administrative intervention. The Supreme Court administration, in a rare move, has formally written to the Union Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA), seeking immediate repossession of the official CJI residence at 5, Krishna Menon Marg. The reason? Justice Chandrachud’s continued occupation of the bungalow beyond the legally permissible period.

At the heart of this situation lies a deeply personal narrative: the former CJI’s two daughters suffer from nemaline myopathy, a rare and incurable genetic disorder that severely affects muscle development. Their ongoing treatment at AIIMS and the logistical demands of their care have led to the delay, as acknowledged by Justice Chandrachud himself. But even amid these exceptional personal circumstances, the Supreme Court has stressed the need to adhere to institutional rules, bringing to fore the nuanced intersection of legal propriety and human empathy.

Exceeding the Allotted Time: The Administrative Tussle

Justice Chandrachud demitted office in November 2024, after a year-long tenure as Chief Justice. Under Rule 3B of the Supreme Court Judges (Amendment) Rules, 2022, a retired Chief Justice is entitled to retain a Type VII residence—not the more prestigious Type VIII bungalow he currently occupies—for a maximum of six months post-retirement.

In December 2024, just weeks after retiring, Justice Chandrachud formally requested permission to continue living at the Krishna Menon Marg residence until April 30, 2025, citing delays in renovation work at an alternative accommodation allotted to him at Tughlak Road. The Supreme Court and MoHUA both agreed to his request, allowing him to stay until April-end, with a caveat that no further extension would be granted.

However, the stay extended into May and eventually July, with a quiet oral request for a further grace period until May 31. That, too, passed. The Supreme Court’s July 1 letter now stresses that both the legal entitlement and the approved extension have lapsed, and has asked the ministry to “take possession without any further delay.”

The Human Side: Special Needs and Delayed Transition

While legal timelines were breached, Justice Chandrachud has been transparent about the personal reasons behind the delay. His daughters, Priyanka and Mahi, both suffer from nemaline myopathy, a severe genetic condition with no known cure. This disorder causes progressive muscle weakness and respiratory difficulties, making accessibility and medical proximity essential to their living arrangements.

Justice Chandrachud explained that although he has been allotted a house on rent by the government, it had been uninhabitable due to disuse and was undergoing renovations—a process delayed by construction bans under GRAP-IV restrictions in Delhi.

“My daughters have severe comorbidities… I totally understand it is my personal issue. But I should also make it clear why it has taken me so long to look for a house, and this is something I have already discussed with the judges and officers in the Supreme Court,” he stated. He emphasized that he remains conscious of his public responsibilities and would vacate “the very next day” the alternate house becomes liveable.

A Unique Precedent: Supreme Court’s Rare Letter

While informal extensions of official residences are not uncommon across top government offices, a formal letter from the Supreme Court’s own administration asking for urgent repossession of the CJI bungalow is unprecedented.

The July 1 communication to MoHUA notes that even the original permission granted for the extended stay had expired by May 31, 2025, and the statutory six-month post-retirement retention period ended on May 10. The letter further underscored the pressure on judicial housing: two sitting judges elevated in recent months are reportedly living in temporary guesthouses due to the lack of availability of permanent accommodations.

This highlights the institutional demand to maintain a functional rotation of official residences and the challenges that arise when exceptions are made—even for the most exceptional reasons.

Rules vs. Reality: Legal Entitlement Under Scrutiny

Rule 3B of the amended 2022 Supreme Court Judges Rules strictly allows post-retirement retention of a Type VII accommodation for six months. Justice Chandrachud was occupying a Type VIII bungalow, typically reserved for the serving Chief Justice.

Though the deviation was approved temporarily due to “special circumstances,” the law remains clear. Beyond six months, any further occupation of such a residence must be vacated, regardless of personal predicaments. By this interpretation, his continued stay is beyond the rule’s scope, prompting the current administrative action.

Justice Chandrachud’s Stand: Conscious, Cooperative, and Awaiting Transition

In his response, Justice Chandrachud has neither deflected nor denied the breach of rules. Instead, he has presented his circumstances candidly, emphasizing that the delay is neither wilful nor indefinite. “It is a matter of just a few days and I will shift… I have occupied the highest judicial office and I am completely cognisant of my responsibilities,” he said.

He also pointed out that he had proactively informed the Supreme Court of the need for an extension in multiple communications, including a letter dated April 28, 2025, seeking time until June 30 due to the special needs of his daughters.

An Administrative Dilemma Rooted in Humanity

The episode surrounding Justice D.Y. Chandrachud’s extended stay at the official CJI residence is emblematic of the friction between procedural rigor and human reality. On the one hand lies the sanctity of legal and institutional norms, on the other, the complex web of personal exigencies involving a former CJI and a family in distress.

The Supreme Court’s insistence on rule-bound administration is justified, particularly when resources are scarce and precedent matters. Yet, Justice Chandrachud’s situation invites a wider reflection on how institutions can accommodate compassion without compromising their framework. As the bungalow’s return now appears imminent, this chapter may well serve as a case study in balancing duty with dignity.

(With agency inputs)